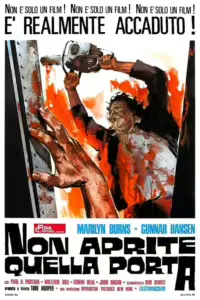

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 50 anni di un capolavoro

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: 50 Years of a Masterpiece

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: 50 Years of a Masterpiece

Five young people on a road trip run out of gas in rural Texas and become victims of a crazed family who kill, butcher, and cook unlucky passing motorists.

It has already been fifty long years since Tobe Hooper’s horrifying masterpiece, and its freshness remains deeply unsettling. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, released in 1974, has not only retained its ability to disturb and fascinate but continues to stand as an unrivaled reference point in the slasher genre.

Hooper’s innovation lies in several aspects. First, the film introduced a raw and ruthless realism that sets it apart from its predecessors. We might call it the unsavory cousin of *Psycho* (a connection that stems from the serial killer Ed Gein, who reportedly inspired both films. Hooper also said the idea came from a doctor who removed the face of a corpse to make a Halloween mask). However, while *Psycho* exudes Hitchcock’s morbid elegance, Hooper’s film carries the anarchic and merciless energy of rural America—a proletarian war zone where revenge is blindly exacted upon the bourgeois youth (whether hippies or future yuppies, it matters little; the sins of the fathers will be visited upon the sons!). Here, society as a whole is horrific (as confirmed by the bleak radio news about rampant violence), projected onto a patch of Texas land where there are no escape routes, laws, or modern civilization.

Hooper’s innovation lies in several aspects. First, the film introduced a raw and ruthless realism that sets it apart from its predecessors. We might call it the unsavory cousin of *Psycho* (a connection that stems from the serial killer Ed Gein, who reportedly inspired both films. Hooper also said the idea came from a doctor who removed the face of a corpse to make a Halloween mask). However, while *Psycho* exudes Hitchcock’s morbid elegance, Hooper’s film carries the anarchic and merciless energy of rural America—a proletarian war zone where revenge is blindly exacted upon the bourgeois youth (whether hippies or future yuppies, it matters little; the sins of the fathers will be visited upon the sons!). Here, society as a whole is horrific (as confirmed by the bleak radio news about rampant violence), projected onto a patch of Texas land where there are no escape routes, laws, or modern civilization.

The rednecks who “hate us” had already made their chilling appearance two years earlier in John Boorman’s small masterpiece, Deliverance. Many of the elements that would make Hooper’s film great were already on the table. In Boorman’s film, too, we feel the dramatic divide between the civilized and those who reject the rules of society, remaining on its fringes.

Perhaps Hooper had also seen and admired Herschell Gordon Lewis’s 2000 Maniacs, a film that begins in a very similar way. Here, the entire community attacks the unlucky Yankees, seeking revenge for the wrongs of the Civil War. Under the Confederate flag, these cinematic maniacs proliferated in the genre, to the point where the “American Gothic” turned into what we can now call “Cannibal Gothic,” often set in rural Texas—the true “final frontier” of American monsters. A primordial place with vast, remote farms where no one can hear you scream.

Hooper filmed on a small budget, using a documentary-style aesthetic, which ties into the narrator’s voice that warns the viewer the event actually happened, creating a sense of reality that amplifies the terror (a common horror technique, as seen in Wes Craven’s debut *The Last House on the Left*). The guerrilla-style filming and use of non-professional actors contribute to the atmosphere of authenticity, making the horror feel close and tangible.

Hooper filmed on a small budget, using a documentary-style aesthetic, which ties into the narrator’s voice that warns the viewer the event actually happened, creating a sense of reality that amplifies the terror (a common horror technique, as seen in Wes Craven’s debut *The Last House on the Left*). The guerrilla-style filming and use of non-professional actors contribute to the atmosphere of authenticity, making the horror feel close and tangible.

Personally, I am firmly convinced that there is something in the film related to Vietnam. Daniel Pearl, the cinematographer, seems to have absorbed the televised coverage of the war, filmed on the ground in 16mm, which was so common in those years. The conflict was still ongoing when the film was released. Perhaps the subconscious of the two filmmakers managed to absorb the atrocities of those dramatic scenes, as there is truly an aesthetic relationship between the film and those army documentary-reportages. Even the unconventional use of sound, like the unsettling buzz of the chainsaw and distorted environmental noises, adds another layer of realism. Hooper and Wayne Bell’s atonal soundtrack, with its metallic clangs and disturbing sounds, amplifies the sense of panic and disorientation for the audience.

A new way of depicting realistic violence in films had been introduced by Wes Craven with his grim rape & revenge *The Last House on the Left*, inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s *The Virgin Spring*. There was something about Craven’s film that troubled audiences and critics—we could call it the “plausibility of violence.” The film was too real, too hard to watch, capable of stirring our basest instincts (Haneke knows this well). So, when the father unleashes his fury in revenge, we are all on his side, wanting to annihilate Krug’s gang forever. It’s at this moment of truth and murderous frenzy that the “chainsaw” appears. Two years later, Hooper would dust off the tool for the occasion.

A new way of depicting realistic violence in films had been introduced by Wes Craven with his grim rape & revenge *The Last House on the Left*, inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s *The Virgin Spring*. There was something about Craven’s film that troubled audiences and critics—we could call it the “plausibility of violence.” The film was too real, too hard to watch, capable of stirring our basest instincts (Haneke knows this well). So, when the father unleashes his fury in revenge, we are all on his side, wanting to annihilate Krug’s gang forever. It’s at this moment of truth and murderous frenzy that the “chainsaw” appears. Two years later, Hooper would dust off the tool for the occasion.

The chainsaw, featured prominently in the title and used by one of the film’s most terrifying characters (Leatherface), would carve out a space for itself in cinema history. Apparently, the director, frustrated by a crowd of people packed into a store during Christmas, saw a rack of chainsaws and imagined using one to escape the store.

In Hooper’s film, the chainsaw serves to make Leatherface appear even more powerful (Gunnar Hansen, the actor behind the mask, was 1.93 meters tall), and Hooper used it intelligently. On one hand, the extreme power of a rotating blade designed to fell trees gives the impression that a true force of nature is crashing down on the unlucky victims. On the other, it makes Leatherface seem “burdened” as he chases the kids, leaving the viewer with a faint hope.

The film is, therefore, an interesting synthesis of works that preceded it, but it’s also innovative in its portrayal of violence. While it doesn’t explicitly show much gore, the “suggestion” of brutality and the viewer’s imagination play a crucial role, far surpassing the special effects of the time. This approach, combined with the depiction of a psychotic cannibal family, left a lasting impact on pop culture and influenced countless subsequent horror films.

According to Quentin Tarantino, it is one of the “perfect” films in cinema history, untouchable. I cannot help but agree, and reflecting on its untouchability, I’d like to add something: the film, material and hallucinatory, has the color of blood that perfectly matches what happens on screen. Even *The Texas Chainsaw Massacre* was shot on 16mm, just like the Vietnam war footage. These films naturally degrade; triacetate (which replaced celluloid because it was too flammable) has a red tint that increases over time. In essence, this film becomes redder, dirtier, and bloodier as it ages, and thinking about this, I’d say we’re witnessing art both within and outside the diegetic universe.

According to Quentin Tarantino, it is one of the “perfect” films in cinema history, untouchable. I cannot help but agree, and reflecting on its untouchability, I’d like to add something: the film, material and hallucinatory, has the color of blood that perfectly matches what happens on screen. Even *The Texas Chainsaw Massacre* was shot on 16mm, just like the Vietnam war footage. These films naturally degrade; triacetate (which replaced celluloid because it was too flammable) has a red tint that increases over time. In essence, this film becomes redder, dirtier, and bloodier as it ages, and thinking about this, I’d say we’re witnessing art both within and outside the diegetic universe.

In short, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is not just a horror masterpiece that should NOT be restored, but also a true cinematic gem that redefined the boundaries of the genre, demonstrating how terror can be effectively conveyed through the skilled use of visual and sound storytelling.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel

Subscribe to our YouTube channel