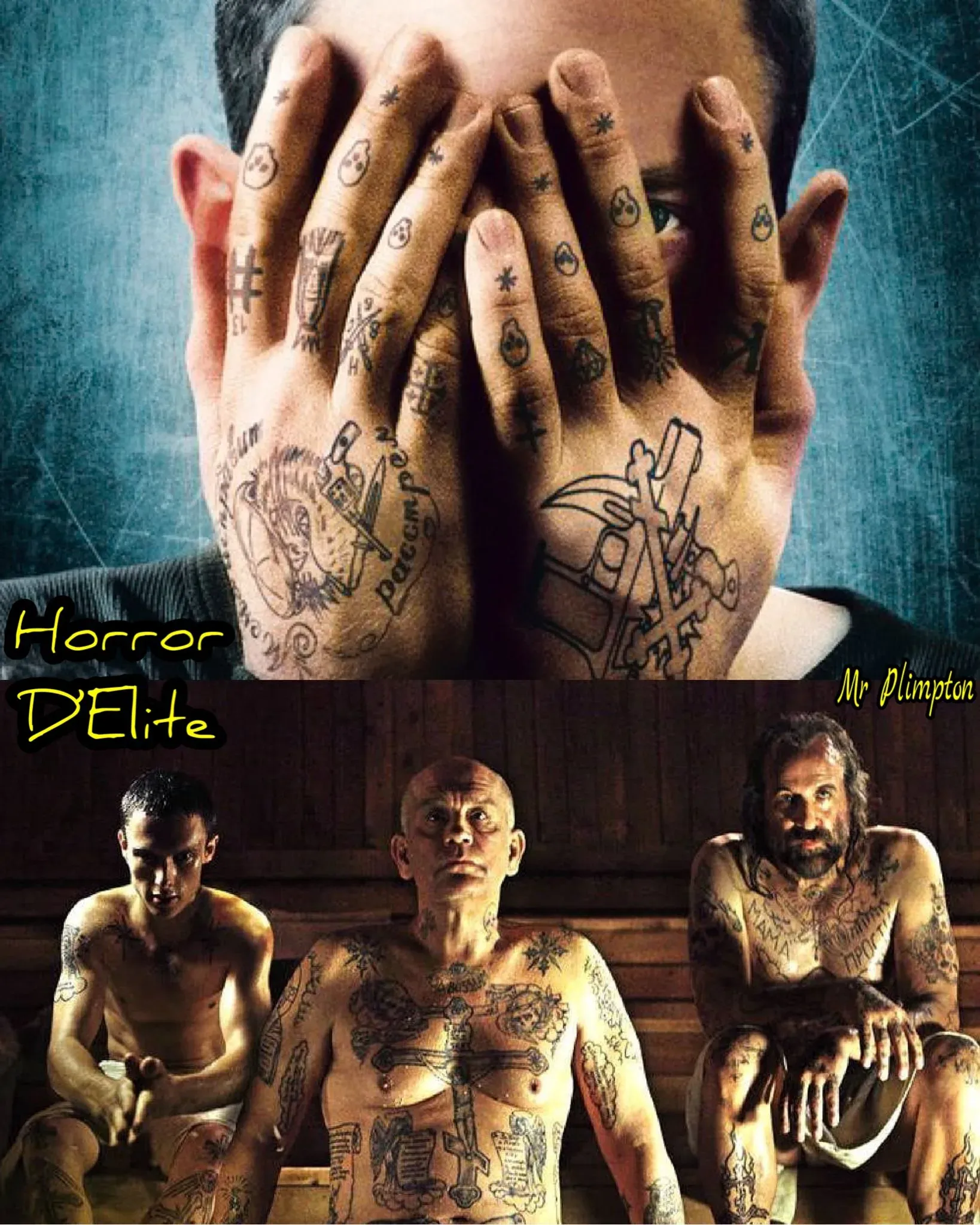

Siberian Education

Siberian Education

by Gabriele Salvatores (2013)

Kolima and Gagarin, best friends, grow up together in southern Russia, in a town that has become a kind of ghetto for criminals of various ethnicities.

Grandpa Kuzja, the head of the Siberian clan, gives them a very particular education based on theft, robbery, and the use of weapons.

All of this is combined with a code of honor that must never be betrayed.

“But remember, we must respect all living creatures.

Except for: the police, bankers, and moneylenders.

Stealing from these people is allowed.”

(Grandpa Kuzja)

The Importance of Tradition.

Education is generally understood as the learning of intellectual and moral principles, in accordance with the needs of the individual and society.

But what happens when you grow up in a place that seems like no man’s land, where the State is completely absent and every behavior is governed by a precise ethical code that admits no distractions?

How vast does the distance become from the rest of the world just a few kilometers away?

These are the most important questions around which the film revolves, this clash between a closed and conservative reality and the modern world that bursts in from the outside with all its revolutionary energy.

Kolyma and Gagarin, under Grandpa Kuzja’s guidance, learn from a young age how to use knives, rob, and move within a criminal community governed by its own laws.

A parallel universe, violent and fierce, full of nuances but also of significant contrasts: a place where cruelty coexists with solidarity, aggression with moments of incredible humanity.

In this regard, the way the community treats anyone unfortunate enough to have physical or mental disabilities is emblematic.

The young daughter of the new doctor, Xenja, who suffers from a slight mental delay, is welcomed like a princess and protected in an almost touching way, because, like everyone in her condition, she is considered “willed by God.”

She will ultimately be the primary cause of the final confrontation between the two protagonists who, as they grow older, adopt opposing views and become bitter enemies.

Considerations

Salvatores has publicly declared his love for this film, his most difficult and ambitious work, with the broadest international scope.

And, indeed, credit must be given to the director for the courage to make such a complex film with a cast composed almost entirely, with three notable exceptions, of first-time Lithuanian actors.

The result is not perfect, but it’s easy to be forgiving when judging a work that puts so much on the table without managing, perhaps due to time constraints, to give proper weight to all the elements it presents.

For example, the fascinating figure of the tattoo artist Ink (Peter Stormare), who teaches the young Kolyma the craft, emphasizing the philosophical meaning of his work, deserved more screen time.

Likewise, the historical events surrounding the narrative are only briefly touched upon.

Starting with post-Soviet Russia and the consequent new nature of society, which increasingly contrasts with the old way of life.

Despite these more or less evident shortcomings, what we are shown remains intense and engaging.

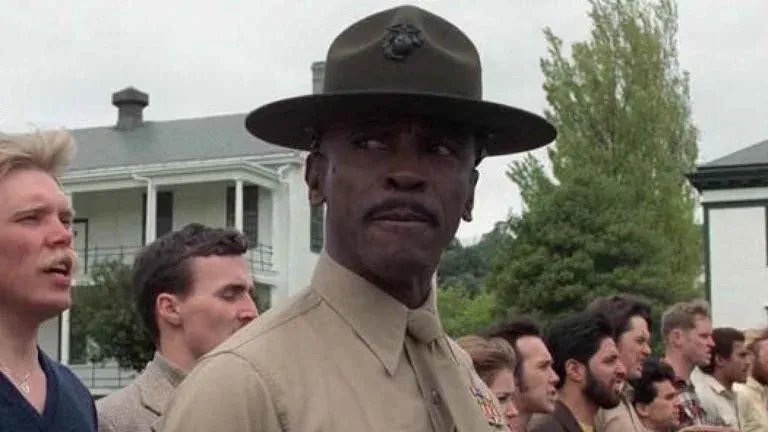

Credit also goes to a remarkable John Malkovich in the role of Grandpa Kuzja, a true life mentor and shaper of new “honest” criminals.

But Eleanor Tomlinson’s surprising performance as Xenja also deserves mention, as she skillfully balances her portrayal without slipping into an overly caricatured representation of her character.

The film’s production is truly excellent, impeccable, and absolutely perfect.

Based on the partially autobiographical novel by Nicolai Lilin.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel

Subscribe to our YouTube channel

Immerse yourself in a world of chills with Nightmares