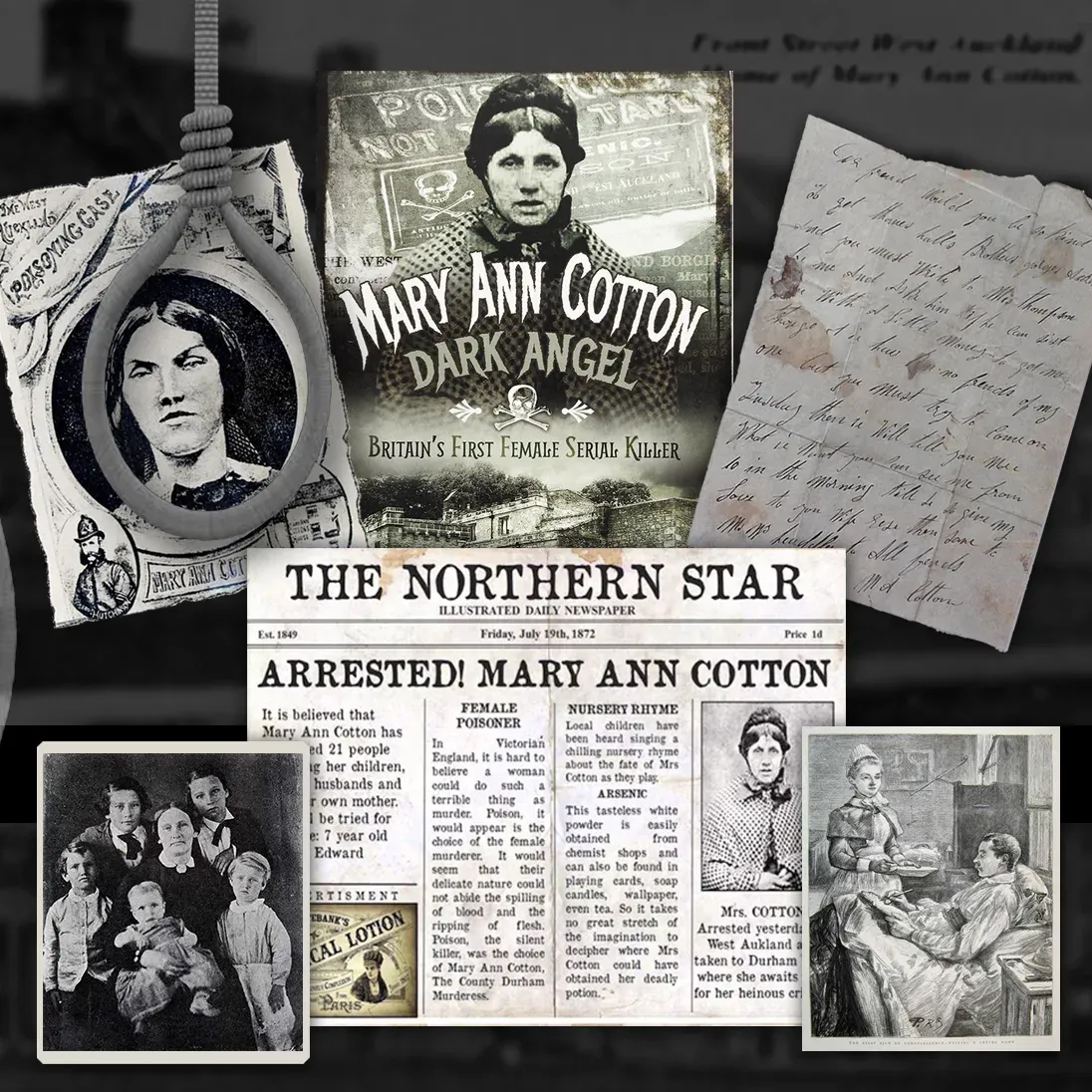

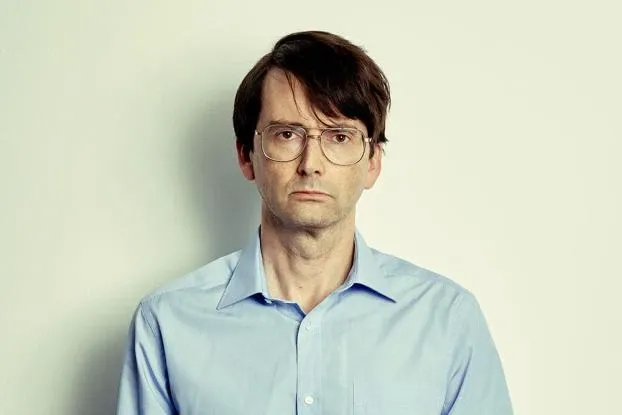

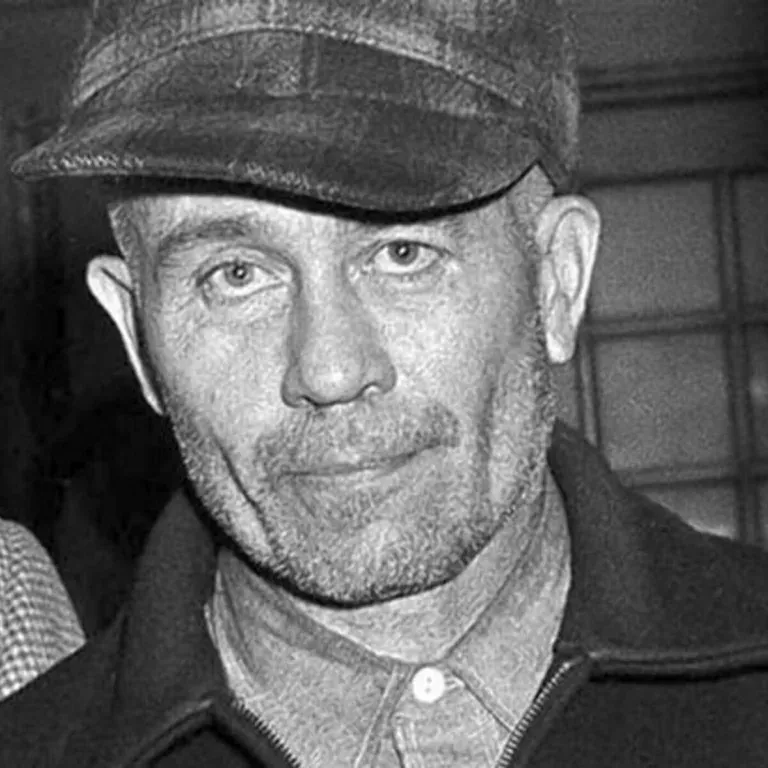

Mary Ann Cotton: The First British Serial Killer

Mary Ann Cotton: The First British Serial Killer, born Mary Ann Robson (Low Moorsley, County Durham, October 31, 1832 – Durham, March 24, 1873), was a British serial killer accused of murdering more than 21 people, mostly using arsenic.

Biography

Mary Ann had a troubled childhood due to her family’s poor conditions, supported by her father Michael Robson’s work as a miner. A Methodist, he raised his daughter with strict discipline.

When Mary Ann was 8 years old, the family moved to Murton, where the girl had difficulty relating to her schoolmates.

Her father died falling into a coal mine pit in Murton on February 23, 1842, when Mary was 10.

Mary Ann was 14 when her mother Margaret Lonsdale (1813-1867) married Robert Scott.

The stepfather continued to impart the principles of strict upbringing, which Mary Ann resisted by leaving the family and going to work as a domestic servant in the home of Edward Potter in South Hetton, a nearby village.

She stayed there for three years until she returned to her mother and decided to learn the trade of a seamstress.

The First Marriage and 8 Children

She met William Mowbray (1826-January 1865), a miner whom she married in 1852 when she was 20.

The couple moved to Plymouth where they had 5 children, four of whom died from gastric fever.

Mary Ann and William returned to the North-East of England where they had three more children who died in early childhood.

William, who had become a pit master and later a firefighter on a steamship, died in January 1865 from an intestinal illness.

Mary inherited £35 from a life insurance policy taken out earlier.

The Second Marriage

After becoming a widow, Mary Ann moved to Seaham Harbor where she began a relationship with Joseph Nattrass, which ended when he married another woman he was already engaged to.

Meanwhile, after the death of her 3-year-old daughter, Mary Ann, left alone, entrusted Isabella, her only surviving child, to her grandmother and moved to Sunderland, where she got a job as a nurse in a dispensary.

There, she met one of the patients, Georges Ward (1833-1866), whom she married in August 1865 in Monkwearmouth.

George, afflicted by a disease characterized by paralysis and intestinal problems, died in October 1866, leaving Mary Ann the beneficiary of a life insurance policy.

The Third Marriage and a Daughter

James Robinson, a carpenter from Pallion, recently widowed from his wife Hannah, hired Mary Ann as a housekeeper in November 1866.

A month later, James’s son died from gastric problems.

Meanwhile, Mary Ann became pregnant by James and, as her mother fell ill, went to Seaham Harbour to care for her.

After an apparent recovery, the woman began to complain of stomach pains and shortly after died at the age of 54 in 1867.

Isabella, who had been entrusted to the grandmother, returned with her mother to Robinson’s home in Pallion, where she died shortly thereafter along with James’s two children (the three children were buried in the last days of April 1867).

Four months later, James formalized his position by marrying Mary Ann, who gave birth to a girl named Mary Isabelle in November 1867. Mary Isabelle fell ill and died in March 1868 at 4 months old.

James began to suspect his wife’s misconduct, particularly her insistence on having him take out a life insurance policy.

Doubts about her character became certainty when he discovered that his wife was in debt for £60, had stolen over £50, which she had likely deposited in the bank, and had pawned several of her valuable belongings.

At this point, James threw Mary Ann out of the house, and she turned to life on the streets.

The Fourth Marriage as a Bigamist and a Son

In this desperate situation, Mary Ann became friends with Margaret Cotton, who introduced her to her brother Frederick, a miner recently widowed and who had lost two of his four children.

Margaret cared for and looked after the two surviving children: Frederick Jr. and Charles Edward until she died in March 1870 from an indeterminate stomach-related illness.

Mary Ann then took on the task of comforting Frederick, who soon got her pregnant and married her in September 1870.

In 1871, the bigamist Mary gave birth to Robert, who died in 1872.

A Relationship and an Illegitimate Child

Soon after, Mary Ann learned that her former lover Joseph Nattrass lived in a nearby town and was no longer married, so she resumed her relationship with him.

Frederick, who had taken out life insurance policies on himself and his children, was struck by a “gastric fever” and died in December 1871.

Nattrass became Mary Ann’s partner, and after she found work as a nurse with John Quick-Manning, a tax agent, she became pregnant by him.

She gave birth to a daughter named Margaret on January 10, 1873, who died in 1953 at the age of 80.

In 1872, Frederick Jr. and Robert died before their father Nattrass, who died from gastric fever after leaving his will in favor of Mary Ann.

A parishioner, Thomas Riley, proposed to help the nurses of a woman affected by smallpox.

Mary Ann replied that she had to take care of the last surviving child of Cotton.

Charles Edward, 8 years old, and asked to have him admitted to the hospital, adding that his health condition would soon lead him to join his siblings.

Riley, who had been a coroner in West-Auckland and had the opportunity to visit the boy, found him in good health, and was surprised to learn of his death a few days later.

Riley then alerted the police to his suspicions and convinced the attending physician to withhold the death certificate until the causes of death were clarified.

The Arrest, Trial, and Conviction

An inquiry was opened during which Mary Ann claimed that Riley had accused her because she had rejected his advances.

The preliminary inquiry concluded that the boy had died of natural causes.

This decision was harshly contested by newspapers, which highlighted the numerous deaths from gastric fever (three husbands, a lover, a friend, the mother, and about a dozen children) of those who had lived with Mary Ann for some time.

This led to a forensic examination that found arsenic in Charles Edward’s body.

Mary Ann was arrested on charges of murder.

The trial, which began on March 5, 1873, was delayed until the defendant had given birth to John Quick-Manning’s daughter, who was later adopted.

The defense argued that Charles had died from inhaling arsenic particles from the wallpaper used in the Cotton household.

They also suggested that the poisoning was due to Mary Ann using a mixture of soap and arsenic to clean the floors, which poisoned the environment.

The jury did not believe these theories and found Mary Ann guilty in just 90 minutes.

The Times Reporter Wrote on May 20, 1873:

“After her conviction, the unfortunate woman appeared to be overwhelmed with emotion, which for a time replaced her usual coldness and reserve.

She is convinced that she will be granted a royal pardon and resolutely maintains her innocence of the crime for which she has been convicted.”

Many petitions for clemency were made to the Home Office, but none were granted.

Mary Ann was hanged in the Durham County prison on March 24, 1873.

The executioner used the technique known as the “short drop,” which caused death not from breaking the neck vertebrae but from slow suffocation.

The Nursery Rhyme

After Mary Ann’s death, a popular nursery rhyme recalled her horrifying figure:

“Mary Ann Cotton

is dead and rotten

lying in the grave

with her eyes wide open.

Sing, sing, what can I sing?

Mary Ann Cotton has a rope around her neck.

Where is she, where is she? Hanging in the air

selling shriveled little hands, a penny a pair”

Subscribe to our YouTube channel