Munch’s Many Screams

Munch’s Many Screams

Edvard Munch’s most iconic work, The Scream, is universally recognized as one of the most powerful representations of human anguish. Less known is the fact that The Scream exists in four different versions, created by the artist between 1893 and 1910. Each version is a unique interpretation of the same theme, revealing Munch’s complex and multifaceted vision of inner torment. Let’s explore the four main versions and the meanings each carries.

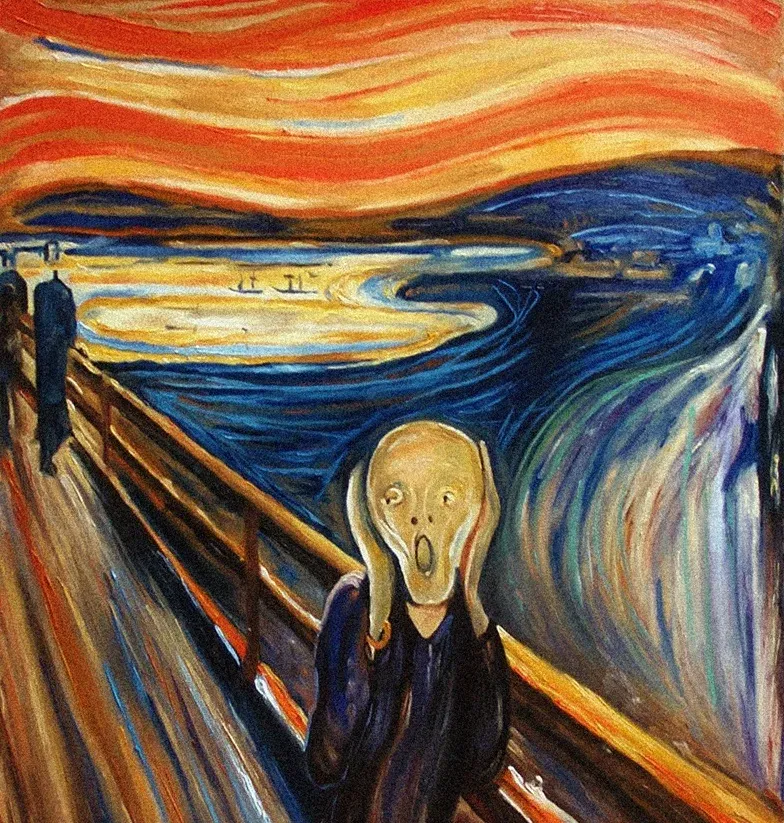

1. The Scream (1893) – Tempera on Cardboard

The first and most famous version of The Scream is the tempera on cardboard, created in 1893. This work is housed in the National Gallery of Oslo. The image depicts a stylized figure writhing on a bridge, surrounded by a fiery, undulating sky that seems to echo its desperate scream. The feeling of alienation and terror is amplified by the use of vivid, strident colors, with the red, orange, and yellow of the sky blending and contrasting with the cooler tones of the landscape. The almost skeletal face of the figure seems to scream not only at the external world but also at a shattered inner reality.

According to Munch, the inspiration for the work came from a personal experience. While walking along a bridge in Oslo, the artist was overwhelmed by a panic attack: “Suddenly the sky turned blood red. I stopped, exhausted, and leaned on the fence. There was blood and tongues of fire above the black-blue fjord of the city. My friends walked on, and I still trembled with fear. I heard a great, infinite scream passing through nature.”

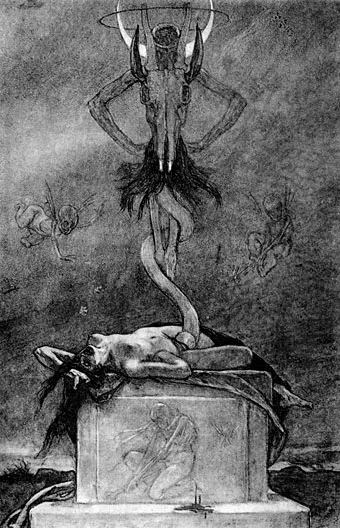

2. The Scream (1893) – Lithograph

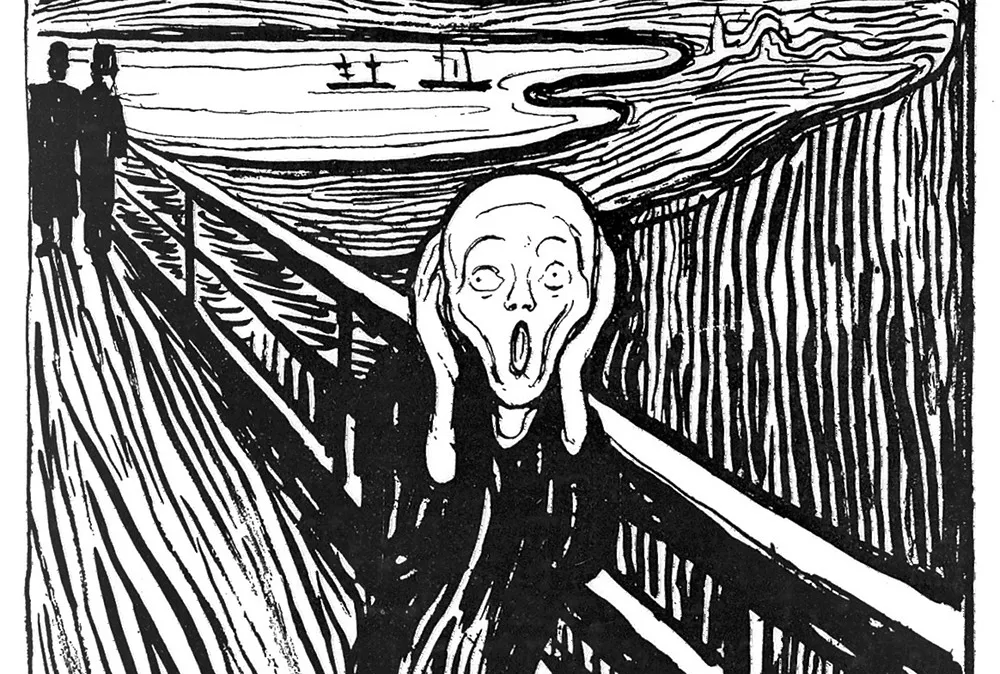

2. The Scream (1893) – Lithograph

Also in 1893, Munch produced a lithograph of The Scream, which became the basis for several subsequent prints. This black-and-white version highlights the dramatic, thin lines of the image, completely excluding color and focusing on the graphic form. The lithograph retains all the drama and tension of the tempera version, but in some way, the black and white accentuates the universal character of the emotion represented, eliminating the chromatic context and allowing the form and expression of the figure to speak on their own.

Being a print, the lithograph allowed Munch to spread his work to a much wider audience compared to a single painting, contributing to making The Scream one of the most recognizable images of the 20th century.

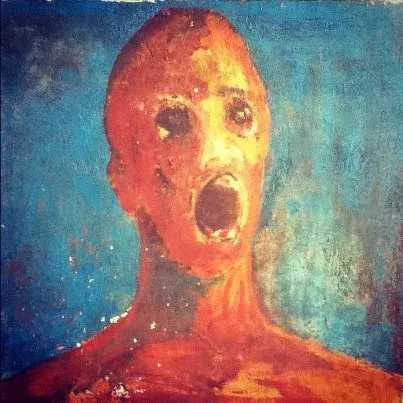

3. The Scream (1895) – Pastel on Cardboard

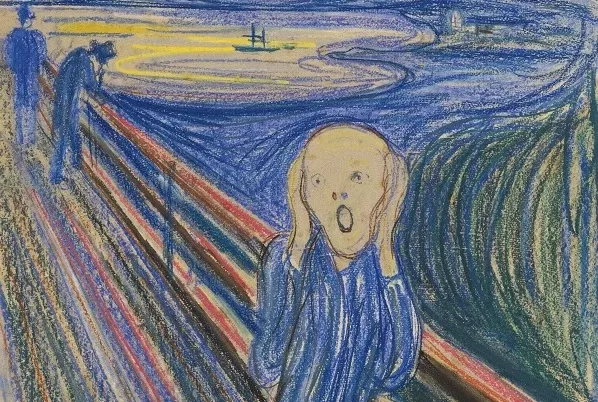

3. The Scream (1895) – Pastel on Cardboard

In 1895, Munch created a version in pastel on cardboard, which is considered one of the most vibrant due to the softer, blended colors that suit the pastel technique. This work is housed in the Munch Museum in Oslo and is known for its emotional impact, despite a softer palette compared to the 1893 tempera.

This version captures a balance between drama and a kind of delicacy, which emerges from the texture of the pastel. The central figure remains the same, immersed in its existential crisis, but the lightness of the shades seems to suggest a scream that dissipates into the air, a suffering less violent but equally penetrating.

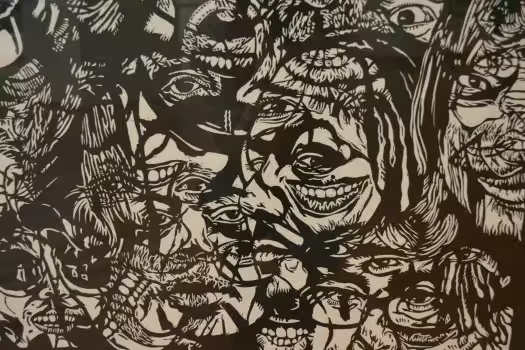

4. The Scream (1910) – Tempera on Cardboard

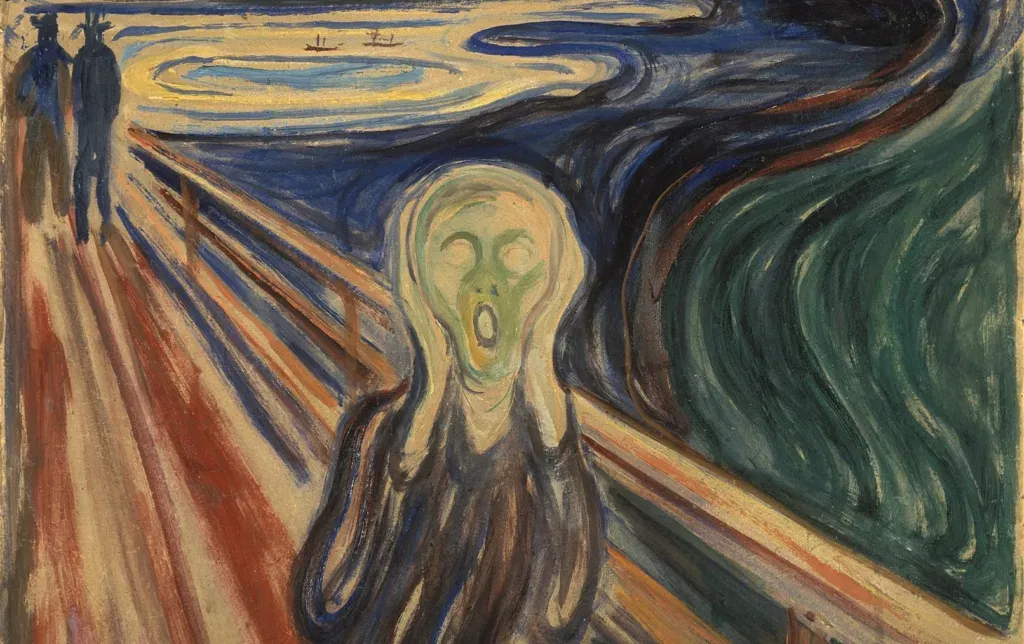

4. The Scream (1910) – Tempera on Cardboard

The last tempera version, dated 1910, is also housed in the Munch Museum in Oslo. This version is visually very similar to the first tempera from 1893 but presents some substantial differences in the treatment of the surface and details. The brushstrokes seem smoother, and the sense of movement is slightly less intense compared to the dramatic turbulence of the sky and waves that characterized the original version.

Despite these stylistic differences, the message of anguish and isolation remains central. Munch, now mature, continues to explore the idea of the human being as a fragile creature, subject to overwhelming emotional forces, always on the verge of bursting into a silent scream. This fourth version marks the end of an artistic and personal process that spanned decades of his life.

Interpretations and Meaning of Munch’s Many Screams

The theme of The Scream connects to Munch’s reflections on human suffering and the alienation of the individual in the modern world. The figure’s scream, which many interpret as a manifestation of anxiety and existential terror, seems to evoke a universal malaise, something that goes beyond individual experience to touch deep chords in the soul of anyone who observes it.

Munch himself was deeply influenced by existentialism and the new psychological theories of the time, such as those of Sigmund Freud. The anguish expressed in his works is partly linked to his personal mental disorders but also represents the drama of man in the face of the immensity of existence.

Conclusion of Munch’s Many Screams

Munch’s Many Screams are not simply copies of the same theme but represent different stages of Edvard Munch’s life and thought. Each one adds nuances to humanity’s cry of anguish, offering a new perspective on one of the most profound and primal emotions: fear. Through these works, Munch not only immortalized his own pain but also gave voice to generations of people who, at least once in their lives, have felt overwhelmed by the unfathomable mystery of existence.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel

2. The Scream (1893) – Lithograph

2. The Scream (1893) – Lithograph 3. The Scream (1895) – Pastel on Cardboard

3. The Scream (1895) – Pastel on Cardboard 4. The Scream (1910) – Tempera on Cardboard

4. The Scream (1910) – Tempera on Cardboard